By FnF Desk | PUBLISHED: 18, Nov 2012, 6:46 am IST | UPDATED: 18, Nov 2012, 11:24 am IST

London: It’s 7.50am on a Thursday in operating theatre four, St George’s Hospital, Tooting, in South West London. A ten-strong medical team is crammed into the small room, but there is a hush in the air.

They are performing a delicate procedure to save 67-year-old Victor Davis’s life: an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair.

An estimated 80,000 men aged 65 to 74 are affected by AAA, when the aorta (the main blood vessel that goes from the heart via the chest, passing through the abdomen and down to the femoral artery in the thigh) weakens and starts to expand like a blow-out on a car tyre.

Undetected, an aneurysm may rupture. This can be fatal: about 6,000 men in the UK die every year in this way. If Victor’s condition had not been picked up, his surgeon estimates it would have burst within a year. Four per cent of all men have an AAA, but most of these will be small and not immediately life-threatening. They are more common in smokers, those with high blood pressure or those with a family history.

Victor was picked up by the new National AAA Screening Programme, introduced in 2009. St George’s was the first hospital to offer screening for all 65-year-old men in their catchment area (women are eight times less likely to have the condition and are so considered low-risk); the programme will cover all of England by March 2013.

Screening is done with a portable ultrasound machine which looks like a laptop and is taken to clinics and GP surgeries in the community by a trained technician who screens about 40 people a day.

Previously, AAAs were picked up incidentally in routine examinations, or seen on X-rays or ultrasound scans done for other reasons. Once found, patients are monitored for an aneurysm’s growth.

Men with a small aneurysm will enter a surveillance programme. Men over 65 who have not been diagnosed with one before can self-refer directly to the programme via a website without going through a GP. It is thought screening could cut death rates by almost 50 per cent.

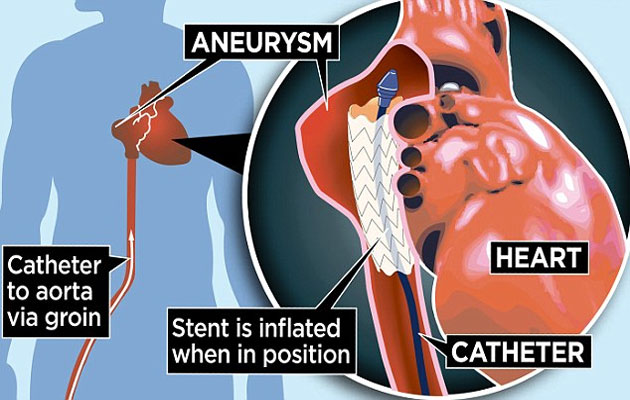

Repairing an AAA was once a major operation that involved opening the chest, with a two-week hospital stay, but recent advances have led to a far less invasive technique. Surgeons use a specially designed stent (a hollow synthetic tube) that is placed inside the aneurysm. Patients can usually go home next day.

As he gets to work on Victor in the operating theatre, vascular surgeon Ian Loftus explains: ‘Our patient has an aneurysm that is 2.7in wide – normal width is 0.7in. With no treatment this would have been likely to burst over the coming year.’ We can see the femoral artery on the X-ray monitor, which shows the surgeon his route to the aorta. The stent is inserted into the aorta through two small incisions made in the femoral arteries, which are accessed through the groin. Some have likened the stent to an inner tube – but made of wire and plastic.

A catheter (fine tube) is used to guide the stent through the aorta to the aneurysm site. The stent is then inflated at the site of the aneurysm and anchored to the normal, healthy artery above and below the diseased portion. This keeps the blood from pushing against the weakened arterial wall, which in turn prevents the aneurysm getting larger.

‘Our survival rates for this procedure are extremely good,’ Ian adds. ‘The old operation was high-risk – actually higher risk than a heart-bypass. Nationally, seven per cent of patients died during or after this operation. Our rate is now below one per cent.’

He marks a point on a monitor to ensure the stent is not pushed too far into the aorta. Then, after it is placed correctly, a device is used to close the artery at the end of the procedure with a cross stitch.

At the end, Ian snaps off his gloves and says: ‘This operation has taken one hour and 17 minutes – previously it would have been a good three hours. The patient will be discharged and home within 24 hours, getting back to normal life, relieved that his AAA is no longer dangerous. Without screening he probably wouldn’t have known he was walking around with this potentially fatal condition.

‘A painless, five-minute test is all it took to make the diagnosis and just a few weeks later he has been treated and is returning to normal.’ The next day, Victor, an environmental officer from Wandsworth, is on his way home with his wife Carole.

He had received the invitation for screening back in 2009 but was reluctant to go. ‘I’d never had a day’s illness in my life,’ he says. ‘I felt fit and well and couldn’t see the point. However, Carole insisted so I booked an appointment at St George’s and was given an ultrasound examination. I was shocked to be told that I had an aneurysm that would rupture at some point and that this is usually fatal. I went for check-ups over the following three years and earlier this year it was too large to wait any longer and I was admitted for surgery.’

Victor was nervous before the operation but it wasn’t as bad as he feared. ‘I was pleased to be able to go home the following day,’ he says. ‘I was back at work in six weeks.’

Victor’s brother also went for a screening and he too had an aneurysm. ‘All men my age should take the screening – it’s far too important not to,’ says Victor.

by : Priti Prakash

In a riveting development in the last 24 hours on October 14, relations between India and Canada plu...