Sao Paulo:

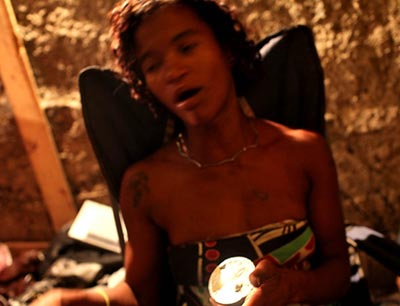

Sao Paulo: Brazil — Glassy-eyed, rail-thin and filthy, hundreds of addicts emerged from doorways and alleys as dusk came to the once-grand Luz district in the heart of this city.

After quick transactions with crack dealers, they scrambled for a little privacy to light up their pipes and inhale tiny, highly addictive rocks that go for about $5 each. The image was reminiscent of Washington or New York in the 1980s, when crack cocaine engulfed whole neighborhoods and sparked a dizzying cycle of violence.

But this time, the crack epidemic is happening in Brazil, alarming officials and tarnishing the country’s carefully cultivated image ahead of two major sporting events to be staged here: soccer’s 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics.

In cities all over Brazil — from this gritty metropolis to the crown jewel of Rio de Janeiro and smaller places in the middle of the Amazonian jungle — nightfall brings out swarms of desperate addicts looking for their next fix in districts known as “cracolandias,” or cracklands.

And like the crack wave that slammed the United States, the result here is the same — lives destroyed, families upended, neighborhoods made uninhabitable.

“Crack is an incurable illness,” said Paulino, 50, a wiry, fast-

talking addict who wouldn’t give his last name as he explained his daily appetite for the drug. “I need crack in my blood. My sickness is like a serpent. What’s the medicine for a serpent?”

With an estimated 1 million cocaine users, Brazil is being whipsawed by a problem that some leaders here once thought of as solely an American one. The trend carries worrisome ramifications for the country, whose population of 200 million includes a booming, new middle class, offering a promising market for traffickers, drug-control experts say.

“In Brazil, we have a similar situation to what happened in the United States in the 1980s,” said Eloisa Arruda, who as secretary of justice for Sao Paulo state coordinates the region’s anti-drug policies. “There’s a big growth in crack use in public and people permanently in the streets consuming drugs day and night who are constantly supplied by traffickers.”

There are key differences: Crack hit U.S. cities that were in decline, buffeting minority communities. The battle over the drug trade also led to a record number of homicides in American cities, as some districts became virtual war zones.

The U.S. response to crack involved locking up addicts and dealers alike, a strategy that filled up American prisons and later led some states to moderate their sentencing guidelines.

Brazilian officials, well aware of the U.S. experience, take great pains to explain that their response to the crack epidemic is different. Although crack is illegal, Brazilian officials view the problem as a public health matter in which the state has a paramount role in helping break addictions.

“We don’t put drug users in prison,” said Leon Garcia, a senior expert on mental health and drugs at the federal Health Ministry. “We have alternative penalties for these people because we don’t believe prisons are the best places to treat them.”

‘They smoke all day’

Out in Sao Paulo’s cracolandia on a recent night, emaciated men, and a few women, crowded around pipes, the soft glow of burning rocks lighting up the darkness. Some huddled under blankets, guarding their precious rocks. Others walked the streets in a frenzy, looking for someone to sell them the day’s ecstasy.

Although police have used sweeps to clear away addicts, on that night, teams of bored-looking officers stood on street corners, watching hundreds of addicts as they got their high.

“This is how it is all day long,” said Isabel Campos, one of several health workers at the site who tried to persuade addicts to seek help. “They smoke all day, use crack all day. And the distribution takes place all day, too.”

On one sidewalk, a man in a red baseball cap and dirty black windbreaker lighted up. He uttered his name, Washington, as one of the outreach workers told him that she wanted him to seek help.

“We are always here if you need us,” she told him.

But he had nothing to say, going back to lighting his pipe, two other addicts at his side.

The reason for crack’s fast spread here remains hard to pinpoint, but law enforcement officials talk of aggressive marketing by drug dealers and of Brazil becoming increasingly appealing to traffickers because of the long, porous borders it shares with the world’s top three cocaine producers.

It is also a country far richer than it was even a decade ago. Thirty million Brazilians joined the middle class, and the country’s solid economy has weathered the worldwide economic crisis. The affluence is everywhere — construction cranes dot urban landscapes, sleek new restaurants open constantly and apartments with bird’s-eye views go for millions of dollars.

“Brazil is a big consumer of cocaine and its derivatives, among them crack, and that’s also due to the buying power of Brazilians in recent years, a growth that’s more apparent in the lower classes,” said Arruda, the Sao Paulo state justice secretary.

Still, even as officials work to showcase the sophisticated new Brazil abroad, the drug underworld in this country has never seemed far.

A potent drug gang in Sao Paulo, the First Command of the Capital, has executed dozens of police officers in recent months. Authorities say drugs are flowing in from Bolivia and Peru, and the national homicide rate remains one of the world’s highest, fueled in part by drug money, said Garcia, the Health Ministry official.

Reaching out to addicts

Officials devising anti-drug strategies say Brazil moved too slowly. Crack appeared here in the early 1990s, drug policy experts said, but it was only since about 2006 that illicit open-air markets began to proliferate.

“This wasn’t given the weight that it should have, but instead was viewed as a small problem,” said Rosangela Elias, who coordinates the city of Sao Paulo’s health programs for crack addicts. “This wasn’t talked about in a serious manner.”

Last December, though, less than a year after taking office, President Dilma Rousseff announced a $1.9 billion prevention and addict-outreach program. The Health Ministry has played a key role.

Thousands of beds are being offered at Psychosocial Attention Centers, of which there are 80 in Sao Paulo, nearly twice as many as in 2005, Elias said.

On a recent afternoon at one of the centers, Antonio Sergio Goncalves, a psychoanalyst who has been working with addicts for 27 years, watched over roomfuls of addicts who had voluntarily come in. Some started out as alcoholics, he said, then moved to ever-stronger drugs before consuming crack.

“The rock works fast, gives them seconds of ecstasy, but it’s seconds, just seconds,” Goncalves said. “The effect passes, and that creates a situation of continued use. These people are easy prey.”

Addict Marcelo Cordeiro, 39, said the feeling is much more intense than when using cocaine.

“Crack gives you euphoria, with morbidity. You know?” said Cordeiro, who was once a chef. “There are intense, intense feelings.”

# Source: The Washington Post, By Juan Forero

Sao Paulo: Brazil — Glassy-eyed, rail-thin and filthy, hundreds of addicts emerged from doorways and alleys as dusk came to the once-grand Luz district in the heart of this city.

Sao Paulo: Brazil — Glassy-eyed, rail-thin and filthy, hundreds of addicts emerged from doorways and alleys as dusk came to the once-grand Luz district in the heart of this city.