Moscow:

Moscow: Snow was falling in the late-night darkness Thursday when a masked figure called out the name of the most influential man at the Bolshoi Ballet — and threw acid in his face. The victim, Sergei Filin, was badly burned, and his sight is threatened.

Evil and betrayal have long played out on the Bolshoi stage, to the enchantment of ballet lovers. By many accounts Friday, they have spilled over into the dancers’ lives and now jeopardize its leadership. Although the motive remains unclear, the attack in central Moscow put a sudden spotlight on festering scandals, battles over artistic vision and historic struggles to shake off the Bolshoi’s Soviet past.

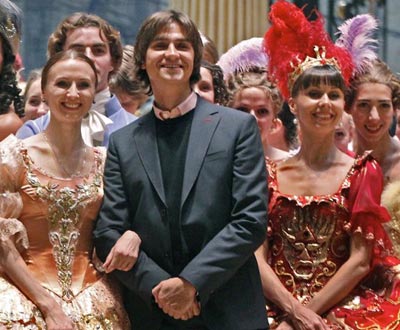

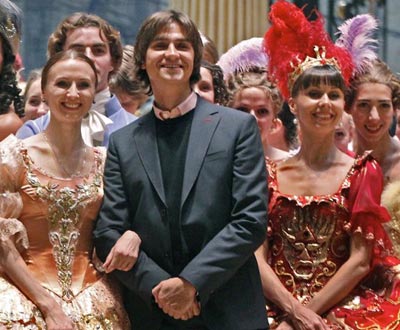

Filin, an acclaimed dancer, ascended two years ago to the all-powerful position of artistic director at the renowned Russian ballet company. In that role, his decisions can propel dancers to stardom or condemn them to oblivion. The institution he oversees is considered a national treasure by the men behind the Kremlin walls, just 500 yards away.

Police and colleagues outlined the bare facts of the crime: Filin, a youthful-looking 42-year-old, was attacked about 11:30 p.m. Thursday as he approached his apartment block, on his return from a theatrical celebration with the city’s glitterati. He suffered third-degree burns and underwent eye surgery Friday, according to Anatoly Iksanov, the Bolshoi’s director. Police said they were searching for a motive connected to Filin’s work, but told the Interfax news agency they did not rule out a dispute over money or property.

Speculation about who was behind the attack — and why — electrified the dance world, where the Bolshoi is known for the technical brilliance, dramatic characterization and high emotion of its performances — and artistic rivalries — rather than for dangerous intrigue.

“In the past they dueled,” said Anastasia Volochkova, a former Bolshoi ballerina, on Ekho Moskvy radio. “People used to cross swords or tried to have it out in a decent way. But splashing acid into the face. . . . This is so low. It’s hard to make any comment.

“What’s happening there is a wild and scary fight,” she said. “It’s a fight for roles.”

Volochkova became known here as the fat ballerina after a previous artistic director at the Bolshoi dismissed her in 2003, accusing her of being too heavy to lift. She weighed 109 pounds at the time, she said.

Filin had been repeatedly threatened in recent days, according to Katerina Novikova, press secretary for the Bolshoi. His tires had been slashed several times, his Facebook page was hacked, and he had received ominous telephone calls, she said.

On Russian television, Iksanov suggested that the attack must be related to Filin’s work. Perhaps someone wanted to set different parts of the company at odds, he said.

People who know the company well unleashed their fury over the assault. It was no accident, said Alexei Ratmansky, who preceded Filin in his Bolshoi post from 2004 to 2008 and now is artist in residence at the American Ballet Theatre. In a Facebook posting, he described how the two-centuries-old Bolshoi was being destroyed by a lack of ethics.

“It’s a loathsome cesspool of those befriending actors, speculators and scalpers, half-crazy fans, ready to bite the throats of their idols’ rivals, cynical hackers, lies in the press and scandalous interviews of staff,” he wrote.

The turmoil that appears to have engulfed Filin began with a dancer and choreographer who took control of the Bolshoi in 1964 and ran it with an unshakable hand for 30 years. Yuri Grigorovich was said to consider communism a higher calling than art, and party bosses were pleased at the expense of the muse. The company was a privileged place to work, where the favored got good apartments and opportunities to tour abroad. But the last years of the Soviet Union brought turbulence, as some dancers agitated for more daring ballets and technique, while others held fast to the old styles.

In 1995, amid reports that the Bolshoi was self-destructing, President Boris Yeltsin intervened, appointing Vladimir Vasiliev as artistic director. Vasiliev, a dashing former dancer, promised he would end the days when roles were won by favoritism or political pull rather than brilliance. He even promised to bring in work from the West.

Four years later, he was out. The Bolshoi was losing stars and luster, and rumors of bitter disagreements swirled. Vasiliev was fired by President Vladimir Putin, reportedly so abruptly that he heard about it on the radio. Putin put the Bolshoi under the control of the Ministry of Culture, and Iksanov was brought in to sort it out.

Yeltsin’s appointment of Vasiliev had enraged Grigorovich, who left in a huff. But his admirers remained, along with rifts that have never quite healed.

Filin began dancing with the company as a young man, and two years ago, returned from the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Music Theater, where he had been artistic director since 2008.

Critics, including The Washington Post’s, liked what they saw. When Filin brought “Coppelia” to Washington last year, the performance got a lovely review.

Filin found a Bolshoi still afflicted by controversy. A six-year-long renovation of its historic building was nearing completion, accompanied by reports of corruption and mismanagement. His immediate predecessor’s contract had not been renewed. The company’s manager, who might have gotten the artistic director job, was taken out of the running after sexually explicit photos were posted online.

Later that year, two bright young stars, Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev, defected to the Mikhailovsky Theater in St. Petersburg, their decision described as a search for artistic growth.

Filin sought change, bringing in an acclaimed dancer from the United States, David Hallberg. The permanent employment of a foreigner was apparently a first in modern times.

But the Bolshoi does not stay quiet for long. Recently, a group of detractors sent a letter to Putin urging him to replace Filin.

Filin offered an upbeat assessment of his work in an interview in the January issue of Dance Magazine. He said he had brought discipline to the company, that he had managed to keep the best of the past while embracing the future. He did not describe himself as loved, but he didn’t seem to mind.

“You know,” he told the magazine, “dancers never like the artistic director. I don’t know the dancers who are happy with their artistic director.”

Moscow: Snow was falling in the late-night darkness Thursday when a masked figure called out the name of the most influential man at the Bolshoi Ballet — and threw acid in his face. The victim, Sergei Filin, was badly burned, and his sight is threatened.

Moscow: Snow was falling in the late-night darkness Thursday when a masked figure called out the name of the most influential man at the Bolshoi Ballet — and threw acid in his face. The victim, Sergei Filin, was badly burned, and his sight is threatened.