London:

London: On 3 March in Sylhet, the acclaimed science fiction writer and academic Zafar Iqbal felt a sharp, painful blow. Foyzur Rahman, a 24-year-old man, had stabbed him in the back. Iqbal collapsed and was rushed to hospital. Rahman was overpowered and later said he considered Iqbal to be an enemy of Islam, continuing the saga of fundamentalist attacks on rationalists in Bangladesh.

Iqbal has often spoken against the fundamentalist threat in Bangladesh. At a human chain protesting the killings of bloggers, he had said: “You will be killed for speaking the truth. We will all be killed for speaking the truth and the government will do nothing. We have to defend ourselves.”

Prompt medical intervention saved Iqbal’s life. After he recovered, he said: “I have no grievance against the assailant. I have forgiven him. It is not enough to punish the attacker. We must ensure that no one follows this path.”

Iqbal’s statement is almost Gandhian. Horace Alexander, the Quaker philosopher who was with M.K. Gandhi in Noakhali in early 1947, recalled an incident when a Muslim man had tried to strangle Gandhi. While collapsing, Gandhi recited a sura from the Qur’an, forgiving his attacker. The stunned man apologized and helped Gandhi get up. Gandhi told him to go back home and not tell anyone what he had done, for otherwise there would be more riots. “Forget me and forgive yourself,” he had said.

There are other parallels. Explaining his feelings as he stepped out of Robben Island after 27 years in prison, Nelson Mandela had said, “As I walked out the door toward the fate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.” Forgiveness helped Mandela leave bitterness behind.

Forgiveness has a practical, pragmatic aspect. For the opposite of forgiveness is the desire to seek revenge, to be angry.

In Anger And Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice, philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes how a working legal system with rule of law cannot be built on retribution. Referring to the way Athena tamed the Furies in ancient Greece in Aeschylus’ Oresteia, she says: “Aeschylus suggests that political justice does not just put a cage around anger, it fundamentally transforms it, from something hardly human, obsessive, bloodthirsty, to something human, accepting of reasons, calm, deliberate, and measured.” If it is not conquered, we get consumed by our own wrath, our own furies. Fury does not salve the wounds; it continues to burn, hurting our inner core, singeing our being. It keeps us bitter, vengeful, and hateful, preventing us from discovering our more humane selves.

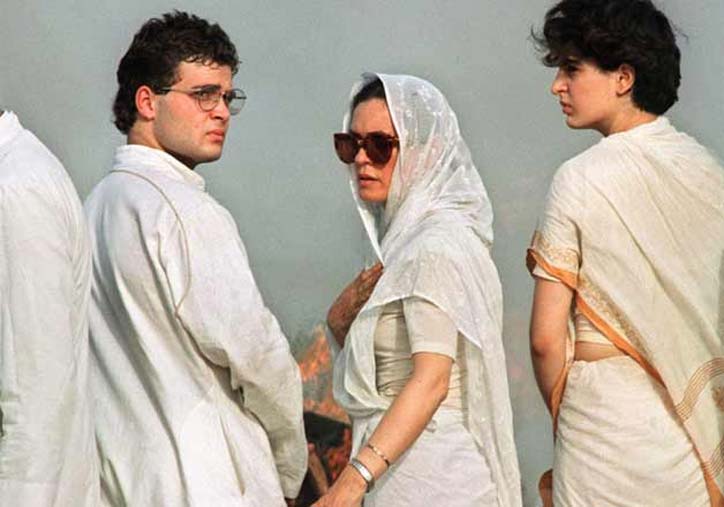

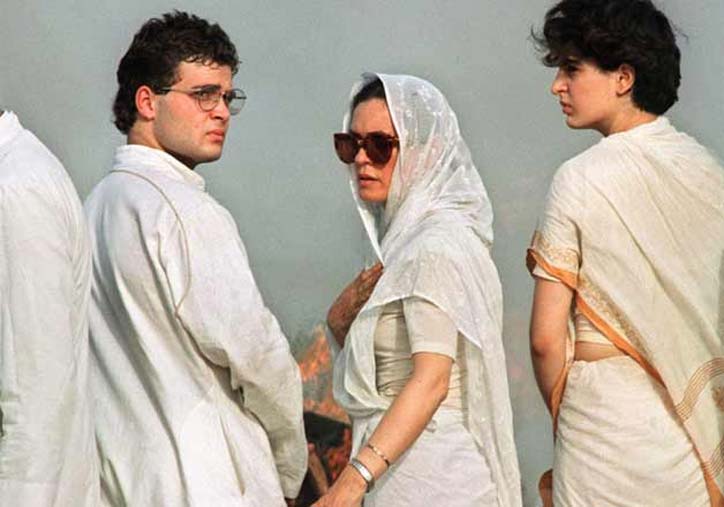

Forgiveness was what Congress president Rahul Gandhi spoke about during his recent visit to Singapore. There was the sideshow that excited networks when a Singapore-based Indian economist asked him about India’s post-independence economic growth. But more profound was his exchange at another event, when another questioner asked if he and his sister Priyanka had forgiven his father’s killers. Rahul Gandhi replied, “We were very upset and hurt and for many years we were quite angry,” but added that they had now “completely forgiven” the killers.

When Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated in 1991, Rahul Gandhi felt a “collision of ideas, forces, confusion”. But when he saw the body of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) leader V. Prabhakaran, he had two thoughts: “One was why they are humiliating this man in this way. And second was I felt really bad for him and for his kids and…. I understood deeply what it meant to be on the other side…. I have been through a lot of pain…and it is something I consider very valuable. I find it difficult to hate people, even my sister does.”

In my conversations with some survivors of violent tragedies, I have seen different reactions. One, in Bangladesh, had said that before she could forgive her father’s killer, the perpetrator had to express remorse first. How can you forgive without any expression of remorse? A South African who had testified at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had told me that the guilty party must make some gesture of atonement first; forgiveness can only be the step that follows. Those are reasonable views. Coaxing forgiveness out of victims of abuse, as some therapists try, so that the victims can “move on”, is wrong.

And yet, unconditional forgiveness can be liberating. It frees the victim to leave the pain behind and not remain caged in the past.

To be sure, anger has its virtues. But anger is meaningful if it seeks justice, not revenge. Aristotle pointed out that being angry against injustice is necessary to right a wrong. The satisfaction that revenge grants, however gratifying, is fleeting: The dead don’t return.

Nussbaum sees value in the perpetrator expressing remorse. As he cleanses his self, he opens space for the survivor to forgive, restoring some balance, even if partly. Holding on to anger can lead to greater catastrophe, Nussbaum argues. To escape the entrapment of the past, the victim has to make the transition from anger, and forgiving the wrongdoer is part of the solution.

Mandela did that, because he wanted to build a better future for South Africa. Gandhi in Noakhali put aside his own pain, because he wanted to stop the fires in India. Zafar Iqbal wants to show potential extremists a better way. Rahul Gandhi, by forgiving his father’s killers, is following that path. That’s where he differs from those obsessed with rewriting our past, because they’re swallowed by ancient hatreds. # Source: The Mint, by Salil Tripathi, Salil Tripathi is a writer based in London.

London: On 3 March in Sylhet, the acclaimed science fiction writer and academic Zafar Iqbal felt a sharp, painful blow. Foyzur Rahman, a 24-year-old man, had stabbed him in the back. Iqbal collapsed and was rushed to hospital. Rahman was overpowered and later said he considered Iqbal to be an enemy of Islam, continuing the saga of fundamentalist attacks on rationalists in Bangladesh.

London: On 3 March in Sylhet, the acclaimed science fiction writer and academic Zafar Iqbal felt a sharp, painful blow. Foyzur Rahman, a 24-year-old man, had stabbed him in the back. Iqbal collapsed and was rushed to hospital. Rahman was overpowered and later said he considered Iqbal to be an enemy of Islam, continuing the saga of fundamentalist attacks on rationalists in Bangladesh.